A salt lick puts Kentucky on the map

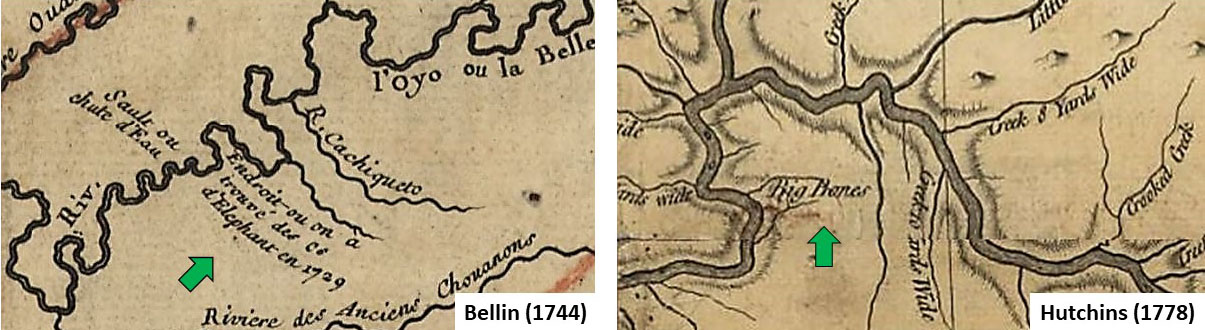

Early maps of the Ohio River region showing notations of elephant bones (Bellin, 1744) and big bones (Hutchins, 1778). Portion of Bellin’s map from the U.S. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. Hutchins’s (1778) map redrafted by Mitchell (1935) in Jillson (1936).

Big Bone Lick is a natural salt spring. Mineral-rich water from deep in the earth comes to the surface at the spring. Many such springs can be found in central Kentucky. These types of springs are called “licks” because animals commonly come to the salty water and salty mud to lick up the salt. Because wild game visited the spring at Big Bone Lick for its salt, Native Americans and then European and Colonial explorers visited the spring to hunt game.

The first European to collect bones from the salt lick was Baron Charles de Longueuil, who led a French army from Montreal down to the Ohio Valley and then down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, claiming much of the region for France. While he was camped on the Ohio River, a group of Shawnee guides brought him bones from what we now call Big Bone Lick. Longueil brought these bones back to France, where they were put in the king’s collection of curiosities. These were the first fossil vertebrate bones collected in North America (Jillson, 1936, 1968).

In subsequent decades the salt lick became known as a place to collect salt and find fossil bones. Bellin’s 1744 map of the “Louisiane lands” [part of which is shown above} includes a notation on a creek of the Ohio River, “Endroit ou’ on atrouve’ der os d’Elephans en 1729,” which translates to “the place where elephant bones were found in 1729.” The date corresponds to Longueuil’s expedition (Jillson, 1936; 1968; Heeden, 2008). A regional map of the British Colonies by Lewis Evans in 1755 includes a notation of a spring and the words “Elephant bones found here” (Jillson, 1936), 37 years before Kentucky became a state.

Map of Kentucky (called “Kentucke” on the map) made in 1785 by John Fillson for George Washington, commander in chief of the armies, with detail showing Big Bone Creek. See explanation in text. Map from Lafon Allen maps collection, University of Louisville, Louisville, Ky.

The occurrence of big bones at the lick was noted on many subsequent European and Colonial maps of the western frontier of North America (anything west of the Appalachian Mountains). The lick’s proximity to the Ohio River, one of the main corridors for western exploration, made it an important stop for hunting and collecting salt to preserve meat. In later years, water from the salt springs was also valued for its supposed medicinal value. Filson’s 1785 map of “Kentucke” shows the location of Big Bone Creek with the notations (1) “Sources Salees,” which translates to “salt spring” or “source of salt,” (2) “Source M’edicinate,” referring to the inferred medicinal quality of the spring water, and (3) “trouve’ les grands Os,” which translates to “discovery [or find] of great bones.”

Related Topics:

- Thomas Jefferson and the birthplace of American vertebrate paleontology

- Benjamin Franklin and the unknown animal

- Georges Cuvier and the concept of extinction

- Ice age mammals, not dinosaur bones

- Reference