Thomas Jefferson and the birthplace of North American vertebrate paleontology

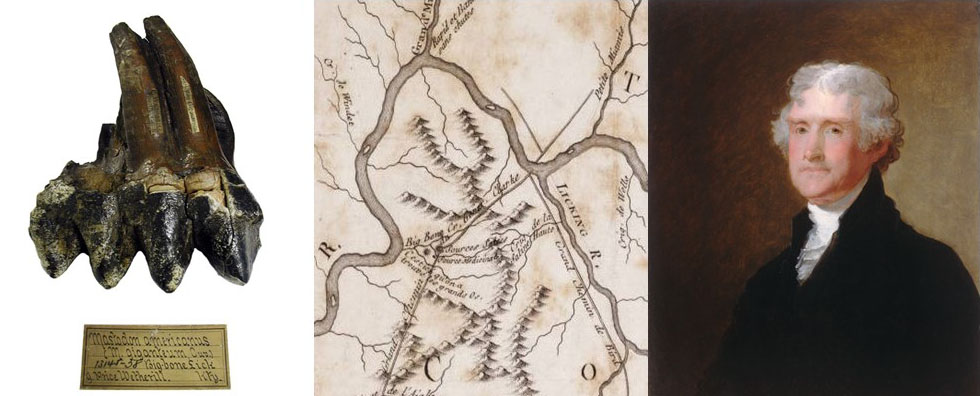

Thomas Jefferson was fascinated by the bones at Big Bone Lick. Mastodon tooth from Jefferson’s Big Bone Lick collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Part of Filson’s (1785) map of the Ohio River, showing Big Bone Lick, from Lafon Allen Maps Collection, University of Louisville, Louisville, Ky. Thomas Jefferson by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1805, oil on panel, National Portrait Gallery.

Not only have modern animals gather at Big Bone Lick, but during the last glacial epoch, ice age mammals also gathered there. Some died at the site, and their bones were buried in layers of mud and clay and then became fossilized. Native Americans were the first to discover and comment about the “big bones” near the spring. Then European and Colonial explorers began to bring back giant bones from the site. Hundreds and possibly thousands of bones were removed by collectors during the mid and late 1700s. The first vertebrate bone ever illustrated from a fossil site in North America was a large molar from Big Bone Lick in a paper on “prodigious teeth” by Urban Sylvanus in 1752. In 1765, George Croghan excavated hundreds of bones from the site and later wrote about his discoveries (Croghan, 1767). These bones were scattered among many collections in Britain and France, and scientists began to describe the large bones (Jillson, 1936, 1968; Cincinnati Museum Center, no date).

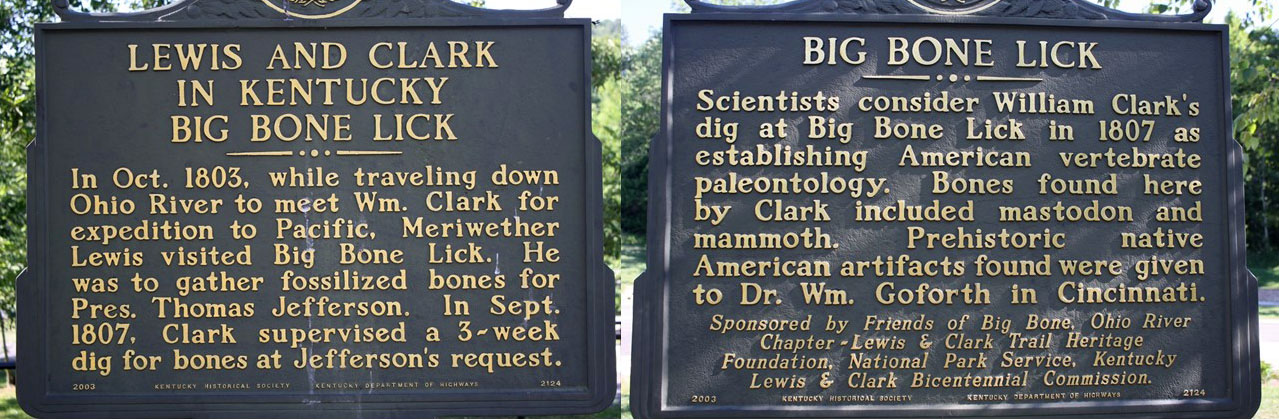

In 1807, President Thomas Jefferson thought the site was important enough that he commissioned Captain William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) to excavate bones from Big Bone Lick for scientific study. This made Big Bone Lick the first funded paleontological excavation in North America. Jefferson paid for the expedition and donated the bones to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia (Jefferson, 1807). Clark collected hundreds of bones from the site. Bones from this expedition can be seen at Jefferson's home Monticello, in Virginia, and in the collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, which he helped found. Although many of the bones from Clark’s expedition were lost, the bones from the 1807 expedition archived in the Academy’s collections remain among the oldest confirmed discoveries from Big Bone Lick. Most of the bones from earlier expeditions have been lost (Schultz and others, 1963).

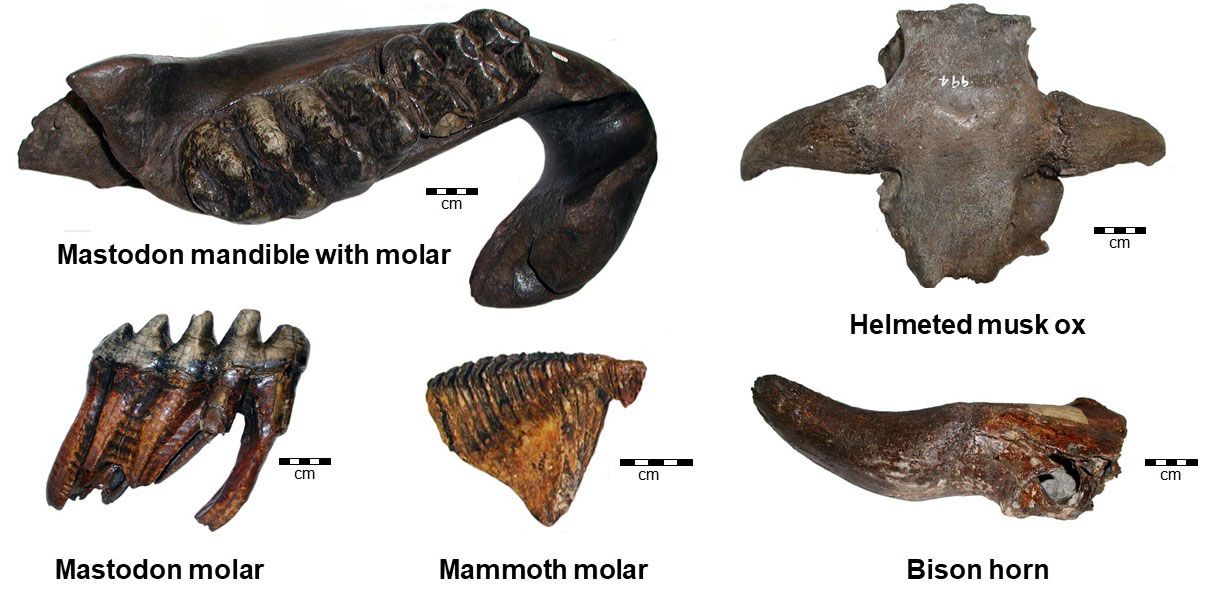

Bones from Thomas Jefferson’s Big Bone Lick collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Photographs by Stephen Greb.

The discovery of "elephant" bones at the lick may have been a supporting reason for Thomas Jefferson sending the explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark westward beyond the wilds of Kentucky (Jefferson, 1787; Lewis and Clark Foundation, 1998). Jefferson was among many scholars who did not accept the concept of extinction (see next section). He thought that the bones from the lick were from American elephants and other species of animals that had not been sighted in the original 13 states, but might be discovered in the great western wilderness. In a letter to the American Philosophical Society, he described mammoths as: “unknown animals as either have been, or hereafter may be discovered in America” (Jefferson and others, 1799; Thomas Jefferson Foundation, no date).

Related Topics:

- A salt lick puts Kentucky on the map

- Benjamin Franklin and the unknown animal

- Georges Cuvier and the concept of extinction

- Ice age mammals, not dinosaur bones

- Reference