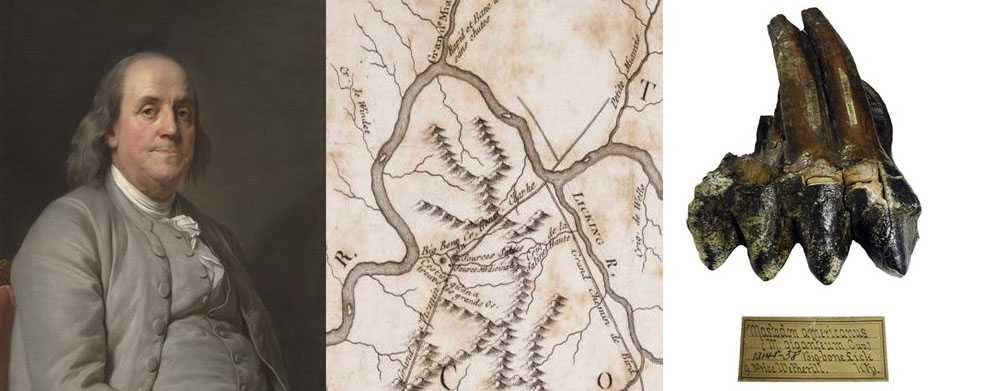

Benjamin Franklin and the unknown animal

Benjamin Franklin studied fossilized bones from Big Bone Lick. Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Duplessis, c. 1785, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery. Part of Filson’s (1785) map of the Ohio River, showing Big Bone Lick, from Lafon Allen Maps Collection, University of Louisville, Louisville, Ky. Mastodon molar, similar to the type of teeth Franklin examined, from Jefferson’s Big Bone Lick collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

During the 1700s, increasing numbers of fossils were being found around the world. Many of these fossils represented parts of organisms that looked different than the shells and bones of modern organisms. Up until then, scientists had thought that all life on Earth had always existed on Earth and always would exist. For example, the bones first brought back for investigation from Big Bone Lick were interpreted to be modern elephants and hippos (see excerpts from letters and articles in Cincinnati Museum Center, no date). Some people even thought the size of the bones indicated that they must belong to a race of human giants that existed prior to Noah’s flood (for example, see Stiles, 1784).

But scientists began to compare the fossil bones to the bones of modern animals (in a new field of study called “comparative anatomy”) and found differences. For example, the British anatomist William Hunter in 1768 thought most of the bones from Big Bone Lick belonged to a single animal, which he called the “animal incognitum” or “unknown animal." Most of the bones were similar to elephant bones, but strange fossil molars with large protrusions were different from those of modern elephants, and must have been from a carnivore. Hence, Hunter envisioned a carnivorous elephant (Hunter, 1768; Benton, 1991; Heeden, 2008). Similar incognitum bones were also found in New York.

Benjamin Franklin was one of the American scientists who studied the bones from Big Bone Lick. He found the bones curious because no living elephant had ever been seen in North America, and there was no mention of elephant-like animals in any of the traditions or stories of the Native Americans. He wrote: “The tusks agree with those of the African and Asiatic elephant … but the grinders differ, being full of knobs, like the grinders of a carnivorous animal … we know of no other animal with tusks like an elephant, to whom such grinders might belong” (Franklin, 1767; Jillson, 1936). After studying the molars, he reconsidered his interpretation of the fossils as representing a carnivorous animal, and wrote in another letter: “It appears to me that Animals capable of carrying such large and heavy Tusks, must themselves be large Creatures, too bulky to have the Activity necessary for pursuing and taking Prey; and therefore I am inclin'd to think these Knobs are only a small variety … and … might be useful to grind the small branches of Trees, as to chaw Flesh” (Franklin, 1768; Jillson, 1936; Heeden, 2008). Franklin appears to have considered the bones to have been from an elephant-like animal that had gone extinct prior to the arrival of Native Americans (Tankersley and others, 2009). Other scientists thought Native Americans had hunted the animals to extinction, or that the animals might still exist elsewhere in the world.

These fossil “elephant” bones were being found in cold temperate climates of North America, northern Europe, and Siberia, even though all known modern elephants live in tropical climates in Africa and India. Franklin hypothesized that it “looks as if the earth had anciently been in another position, and the climates differently placed from what they are at the present” (Franklin, 1767; Jillson, 1936, 1968; Heeden, 2008)—145 years before the concepts of continental drift and plate tectonics.

Related Topics:

- A salt lick puts Kentucky on the map

- Thomas Jefferson and the birthplace of American vertebrate paleontology

- Georges Cuvier and the concept of extinction

- Ice age mammals, not dinosaur bones

- Reference