Georges Cuvier and the concept of extinction

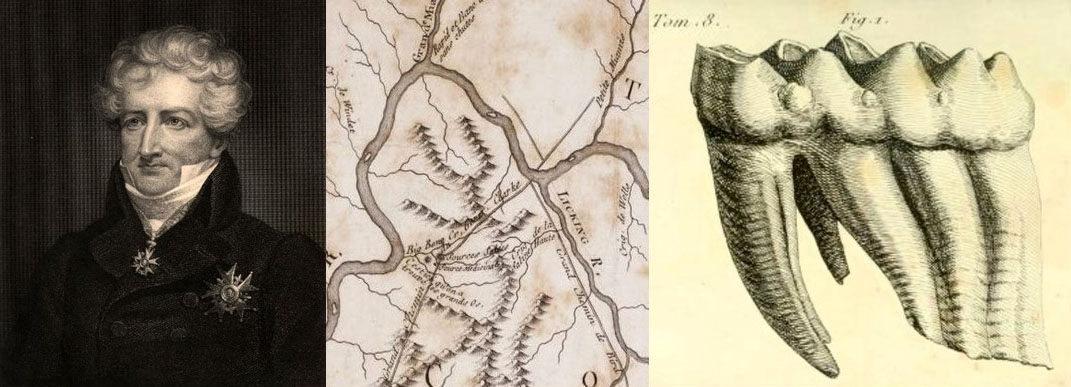

Georges Cuvier studied fossilized bones from Big Bone Lick and other parts of the world, using the bones to define and interpret mastodons as a type of extinct elephant. Georges Cuvier by James Thompson, c. 1800 engraving, Smithsonian libraries image. Part of Filson’s (1785) map of the Ohio River, showing Big Bone Lick, from Lafon Allen Maps Collection, University of Louisville, Louisville, Ky. Drawing of a mastodon molar from Big Bone Lick in Cuvier’s 1806 manuscript on mastodons.

In the late 1700s, fossil bones were being discovered that did not appear to be the same as the bones of known living animals. The concept of extinction had not been developed. Scientists thought that animals on the earth had always existed since they were created. Georges Cuvier was a naturalist and scholar at the National Museum in Paris. He was the right person at the right place at the right time. Cuvier developed the concept of comparative anatomy and began to compare body parts and functions of body parts in the vast array of vertebrate bones that had been brought from around the world by French ships to the museum in Paris. Because of the large number of modern bones at his disposal, he could make detailed comparisons, not only between the different bones of modern animals, but also with fossilized bones being brought to his museum.

In 1796, Cuvier presented a paper comparing the bones of modern African and Indian elephants with fossil bones of elephants (now called mammoths) from Europe and Siberia and the “animal de l’Ohio” from Big Bone Lick. The “animal from the Ohio,” had bones and tusks that were similar to, but different than, modern elephants. Most different were the cheek teeth, which had conical knobs on them. He concluded that the fossil bones were not the same as those from living elephants, and hence were from animals that no longer existed. They must have been extinct, because much of the world had been explored by the late 1700s and these animals were too large to have remained hidden. In subsequent years he published on other extinct animals, including ground sloths, pteradactyls, and mososaurs, cementing extinction as a valid scientific concept.

In 1806, Cuvier published a study on the “animal from the Ohio” in which he gave it the name Mastodonte, which means “breast” or “nipple” tooth in Latin. The name was derived from the conical knobs on the molar teeth of what we now call a mastodon. The report was reprinted in Cuvier’s 1812 “Research on Fossil Bones.” Fossils from Big Bone Lick had actually been given the scientific name Mammut Ohioticum [in modern scientific notation, species are lower case, but in the 1700s and 1800s species names were often capitalized] a few years earlier by the German scientist Johann Blumenbach (1797). (Also see Jillson [1968]). Because the first scientific name published has precedence, the modern scientific name for the mastodon is Mammut, although informally the name “mastodon” is still used. The informal name helps to make a clear distinction between the mastodon and the other type of ice age elephant found at Big Bone Lick and parts of Europe and Siberia, the mammoth (scientific name: Mammuthus, which is similar in spelling to Mammut).His detailed comparisons of mastodon, mammoth, and elephant bones showed they were distinctly different animals. Many species of extinct mastodons and mammoths are now known.

In 1813, he formally published his “Essay on the theory of the earth” in which he not only showed that many fossils were the remains of extinct animals, but he also postulated that there had been many catastrophic events in earth history which had caused extinctions. We now know that most fossils represent extinct organisms. We also understand that there have been many extinctions in earth history, with a variety of causes. These ideas, however, began by carefully studying fossils, including some strange fossil bones from Big Bone Lick, Kentucky.

Related Topics:

- A salt lick puts Kentucky on the map

- Thomas Jefferson and the birthplace of American vertebrate paleontology

- Benjamin Franklin and the unknown animal

- Ice age mammals, not dinosaur bones

- Links to more information about mass extinction

- Reference