Phosphate Mining

The Lexington Limestone contains unusually high concentrations of phosphate (Cressman, 1973). Phosphate minerals occur in most members of the Lexington Limestone, but have relatively higher concentrations in parts of the Tanglewood, Millersburg, and Grier Limestone Members. Although commonly called collophane, the phosphates are actually cryptocrystalline apatite, a calcium phosphate. The phosphates occur within the matrix of the limestones, with concentrations of 10.8 to 2.4 weight percent phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), usually as coatings and crusts along hardgrounds or as infillings of pore spaces in fossil grains, with replacement of preexisting calcium carbonate in crinoids (Cressman, 1973).

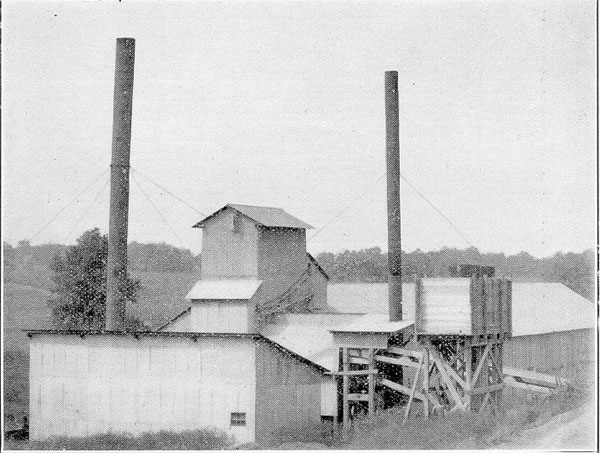

Mining occurred in the early 1900's in central Kentucky, principally around Wallace Station in northern Woodford County. Much of the mining was centered on phosphates concentrated in residuum in solution features and fractures on and in the bedrock limestone of the old upper Benson and Woodburn Formations (Foerste, 1913; McFarlan, 1943; Black, 1964), which would be the Grier Member and middle Tanglewood Limestone Member of the Lexington Limestone as mapped today (e.g., Pomeroy, 1970).

High phosphate concentrations occur in limestones and soils above certain members of the Lexington Limestone across most of central Kentucky (McFarlan, 1943). This region occurs at the apex of the Jessamine Dome, a broad structural high that is part of the Cincinnati Arch. Similar deposits are also known to occur in limestones on the Nashville Dome in Tennessee, which is another structural high along the Cincinnati Arch (Cressman, 1973).

The fact that phosphates occur on two of the structurally high parts of the Cincinnati Arch suggests that those parts of the arch must have played an important role in concentrating the deposits. The Lexington Limestone formed in the Late Ordovician, when what is now central Kentucky was covered by a shallow, tropical sea. Because phosphates are most common in deep oceanic waters, we know that the phosphates in the Lexington Limestone formed in deeper waters off of the Cincinnati Arch, and then were concentrated on the Jessamine Dome part of the arch. The phosphates on the Jessamine Dome are mostly concentrated in the Tanglewood Member of the Lexington Limestone, which was deposited as shallow water carbonate shoals (Cressman, 1973; Ettensohn, 1992; Koirala and others, 2016). Research suggests that fault reactivation along the Jessamine Dome during deposition of the Lexington Limestone may have been the reason it was a paleotopographic high on which shoals could build up through time (Ettensohn, 1992; Ettensohn and Kulp, 1995; Ettensohn and others, 2004).

Through time, the Lexington Limestone was buried, and then later exposed by erosion. Long weathering and erosion led to deposits of residuum that concentrated phosphates in local areas even further, forming the historically mined areas of central Kentucky. Mining stopped in the 1920s (Foerste, 1913; Phalen, 1915; McFarlan, 1943), but the natural phosphates in the limestones remain, and continue to be leached into the overlying soils.

Phosphates are a natural source of nutrients and fertilizer, which have long been known to benefit Bluegrass soils (e.g., Foerste, 1913) and is one of the reasons central Kentucky is a center for the Thoroughbred horse industry. These naturally occurring phosphates help build strong bones in mammals.

Although a boon to central Kentucky's soil fertility, many of the phosphate-rich soils and limestones in the Bluegrass Region also emit locally high levels of radon. Radon is a daughter product of naturally occurring uranium minerals found in phosphates. Radon is a health concern because it has been linked to lung cancer. To learn more about radon go to the KGS radon page.

References

Black, D.F.B., 1964, Geologic the Versailles quadrangle, Kentucky: U.S. Geological Survey, 7.5-minute geological quadrangle map, 1:24,000, GQ 325, one sheet.

Cressman, E.R., 1973, Lithostratigraphy and depositional environments of the Lexington Limestone (Ordovician) of central Kentucky: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 768, 61 p.

Ettensohn, F.R., 1992, Regressive facies in the upper Lexington Limestone: Tanglewood–Millersburg relationships, in Ettensohn, F.R. (ed.), Changing Interpretations of Kentucky Geology—Layer-Cake, Facies, Flexure, and Eustacy: Ohio Division of the Geologic Survey, Miscellaneous Report, v. 5, p. 62–66.

Ettensohn, F.R., and Kulp, M.A., 1995, Structural–tectonic control on Middle–Late Ordovician deposition of the Lexington Limestone, central Kentucky, in Cooper, J.D., Droser, M.L., and Finney, S.C. (eds.), Ordovician Odyssey: Short Papers for the Seventh International Symposium on the Ordovician System. Pacific Section: Society for Sedimentary Geology (SEPM), Fullerton, p. 261–264.

Ettensohn, F.R., Kasl, J.M., and Stewart, A.K., 2004, Structural inversion and origin of a Late Ordovician (Trenton) carbonate buildup: evidence from the Tanglewood and Devils Hollow members, Lexington Limestone, central Kentucky (USA): Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, v. 210, no. 2-4, p. 249–266.

Foerste, A.F., 1913, The phosphate deposits in the upper Trenton limestones of central Kentucky: Kentucky Geological Survey, ser. 4, v. 1, pt. 1, p. 391–439, illus.

Koirala, D.R., Ettensohn, F.R., and Clepper, M.L., 2016, Eustatic and far-field tectonic control on the development of an intra-platform carbonate-shoal complex: upper tongue of the Tanglewood Member, Upper Ordovician Lexington Limestone, central Kentucky, USA: Sedimentary Geology, v. 345, p. 1–18.

McFarlan, A.C., 1943, Geology of Kentucky.

O'Dell, G.A., 2018, At the starting post: Racing venues and the origins of thoroughbred racing in Kentucky, 1783-1865: The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, v. 116, no. 1, p. 29-78.

Phalen, W.C., 1915, Report on the phosphate rocks of central Kentucky: Kentucky Geological Survey in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey, 80 p., illus.

Pomeroy, J.S., 1970, Geologic map of the Midway quadrangle, central Kentucky: U.S. Geological Survey, 7.5-minute geological quadrangle map, 1:24,000, GQ 856, one sheet.