Limestone Industry

Limestone

Central Kentucky

Continuing growth in commercial, residential, and highway construction industries creates a strong demand for construction aggregate in central Kentucky. The term aggregate refers to the hard, inert rock particles that are combined with binding materials to form cement concrete and asphalt concrete, or are used alone (for example, as road base).

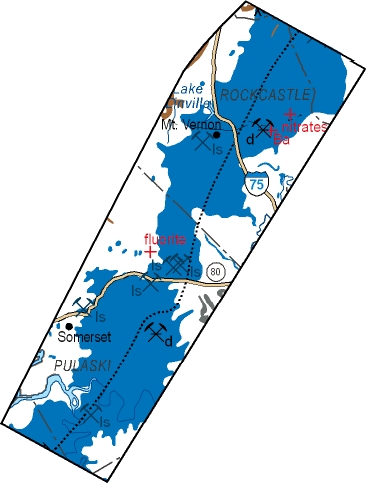

In central Kentucky, Ordovician limestone and dolomite are mined and quarried for construction aggregate. Stone is being produced from the High Bridge Group and the overlying Lexington Limestone. The High Bridge Group consists of three formations: in descending stratigraphic order, the Tyrone Limestone, Oregon Formation, and Camp Nelson Limestone. Only the Grier-Curdsville and Tanglewood Members of the Lexington Limestone are mined.

High Bridge rocks, 470 to 570 feet thick, are composed of dense, micrograined limestone and finely crystalline dolomite. The Lexington Limestone, 180 to 320 feet thick, contains a variety of carbonate lithologies, but is mainly fine- to coarse-grained, partly shaly, fossiliferous limestone. The High Bridge Group is the region's principal source of aggregate; stone is produced from nine underground mines and one open-pit quarry. Lesser quantities of aggregate are obtained from four quarries and one mine operating in the Lexington Limestone.

The geologic and topographic position of the Ordovician deposits determines the method of production. Lexington limestones crop out at the surface in central Kentucky, and are mainly produced from open-pit quarries. High Bridge rocks lie below the surface across most of the region, and are principally exploited by underground mining. As a result of uplift along the Cincinnati Arch, vertical displacement along faults, and downcutting by the Kentucky River, High Bridge deposits are exposed along entrenched valleys of the river and its tributaries, from Boonesborough downstream to Frankfort.

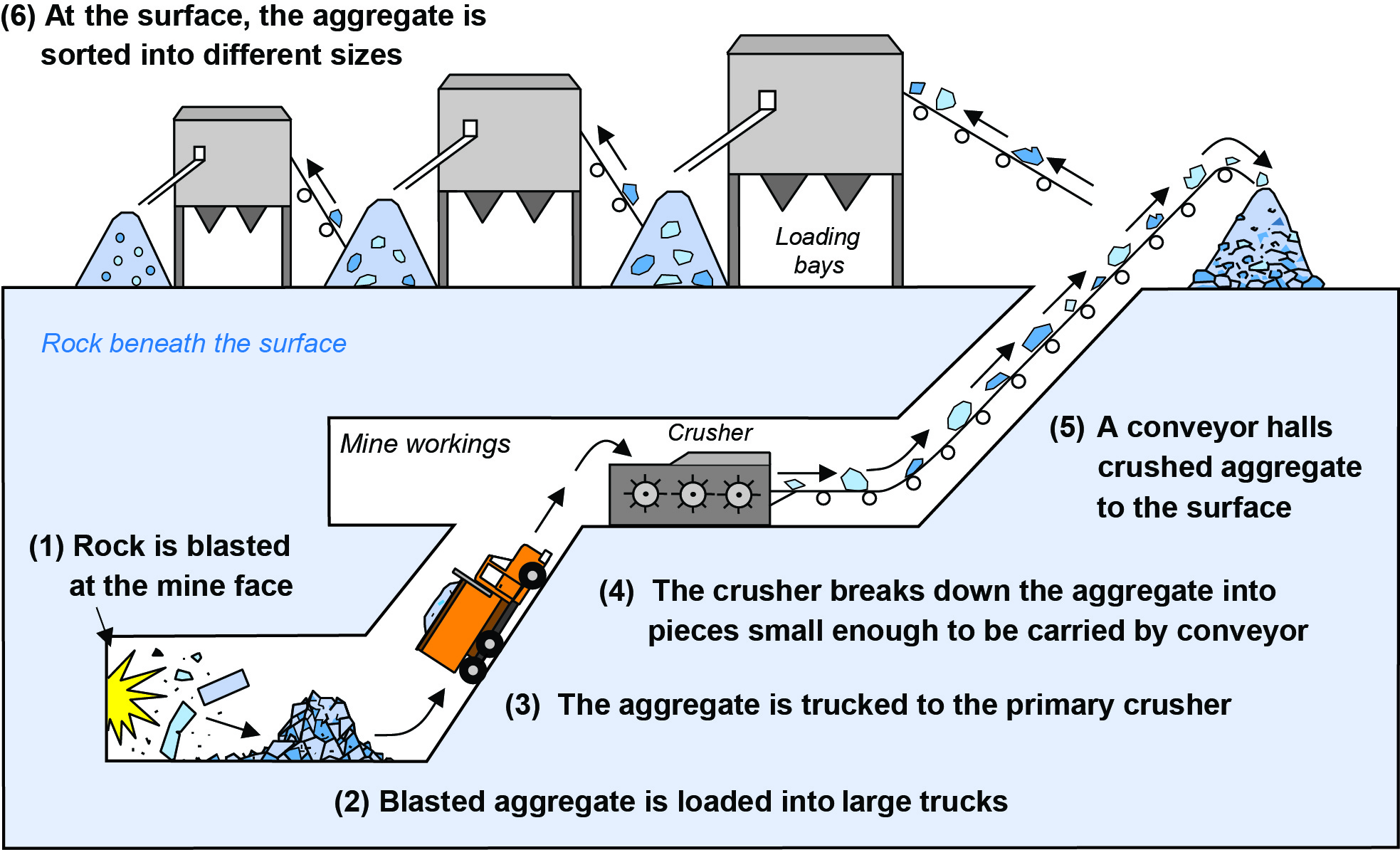

Two of the underground operations in the High Bridge are drift mines and seven are slope mines. The drift mines are driven horizontally into High Bridge rocks exposed in cliffs along the Kentucky River Valley. In the slope mines, an inclined entry is opened from the surface down to the mining interval. Several slope mines in the High Bridge originally were the site of open-pit quarries in the Lexington Limestone. After reserves of Lexington Limestone on the property were exhausted, an inclined slope was driven down into the underlying High Bridge limestone and dolomite to produce stone by underground mining.

High Bridge limestone and dolomite in the lower Tyrone Limestone and Oregon Formation, an interval about 60 feet thick, commonly have been mined in central Kentucky for aggregate. At several mines, after the lower Tyrone and Oregon reserves were exhausted, an inclined slope was driven down into the underlying Camp Nelson Limestone to produce stone from another interval in the High Bridge Group, bypassing deleterious argillaceous limestone and shale in the uppermost Camp Nelson. Thus, on some properties in central Kentucky, stone has been produced from two and three levels.

Underground operations close to urban markets offer the advantages of requiring less high-cost urban land and producing less surface noise and dust than open-pit quarries. Underground mining also has the potential for year-round operation and avoids high costs for overburden removal and reclamation.

The High Bridge Group is a major source of construction aggregate because the limestone and dolomite have suitable physical properties, mainly resistance to abrasion and resistance to disintegration from weathering. High Bridge rocks in part have a high carbonate content (CaCO3 + MgCO3) and low silica (SiO2) and alumina (Al2O3) contents. Carbonate rocks with these chemical characteristics are suitable for industrial and agricultural uses (Dever, 1980, 1981, 1990; Dever and others, 1994).

Two mines along the Ohio River in north-central Kentucky (Outer Bluegrass Region) are producing stone from the Camp Nelson Limestone for the manufacture of low-magnesium and high-calcium limes. The limes are used for flue-gas desulfurization at coal-fired power plants, and for steel-furnace flux, chemical manufacture, and water treatment. Camp Nelson limestone mined in central Kentucky is also used for agricultural limestone, fertilizer filler, and rock dust for explosion abatement in coal mines.

Western Kentucky

Large reserves of limestone suitable for a variety of industrial uses are located in western Kentucky, stretching from Brandenburg in Meade County through Bowling Green in Warren County to Smithland in Livingston County. The major lithologic units in the area are the Mississippian Meramecian limestones, including the Fort Payne Formation and Warsaw, Salem, St. Louis, and Ste. Genevieve Limestones. High-calcium limestone zones occur within the Warsaw and Ste. Genevieve Limestones. The large areal extent of the Ste. Genevieve makes it a valuable source of limestone in Kentucky. Deposits located close to transportation routes, particularly river transportation, are vital to a large, viable mining operation. The Ste. Genevieve primarily occurs in Meade County, but also in parts of Caldwell, Calloway, Christian, Crittenden, Livingston, Lyon, Marshall, and Trigg Counties. These areas are located close to major navigable waterways and major Interstate highways.

The Warsaw Limestone contains thick deposits of high-calcium limestone and is a medium gray, fine- to coarse-grained limestone containing fossil material in a chalk-like matrix. Other parts of the Warsaw may be high calcium but are not as pure a limestone.

The Salem and St. Louis Limestone are suitable for general construction aggregate, but probably have limited value as a high-calcium stone, but a small interval in the lower part of the upper St. Louis has almost 95 percent calcium carbonate content.

The Ste. Genevieve is a good source of high calcium limestone. The Ste. Genevieve covers a large area in western Kentucky, but finding sites near the navigable waterways is more challenging. The occurrence of mineable limestone in the Ste. Genevieve is related to the occurrence of oolitic limestones, which account for the high-calcium deposits. The Fredonia, Rosiclaire, and Levias are strategic markers in the Ste. Genevieve. Part of the outcrop belt near Princeton is broken by faulting along the Rough Creek Fault System.

Oolitic and bioclastic limestones are typically mined in western Kentucky.

Three limestone mining operations are active in the area: Marion Quarry in Marion, operated by the Rodgers Group Inc.; Three Rivers Quarry in Smithland, operated by Martin Marietta Aggregates; and Grand Rivers (formerly Reed) Quarry in Gilbertsville, operated by Vulcan Construction Materials. The Grand Rivers Quarry is one of the largest crushed stone quarries in the United States and is the leading producer of stone in Kentucky. These quarries combine to produce millions of tons of stone annually, most of which is shipped to consumers along the Ohio River.

Eastern and South-Central Kentucky

The St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve Limestones are two major Mississippian units that produce significant limestone resources in eastern and southeastern Kentucky. The St. Louis is divided into two units: the Bronston and Burnside Members (Dever and Moody, 2002) in southern Kentucky and the Slade Formation (Sable and Dever, 1990), formerly called the Newman Limestone, in many parts of eastern Kentucky. The Slade Formation encompasses many varied carbonate units, but they will be described as the Slade in this discussion.

The Newman Limestone crops out along the Pine Mountain Thrust Fault in southeastern Kentucky, and several mines have been opened to provide high-calcium stone for the rapidly growing area. High-calcium, low-silica stone occurs in the Newman and can be used as rock dust for explosion abatement and for acid mine-drainage control. Five mines have been opened in the Newman along the Pine Mountain Fault, and although mining is complicated by the steeply dipping rocks and faulting along the thrust, these mines produce millions of tons of stone per year.

Dolomite

Dolomite resources occur in Devonian and Silurian rocks in a large area around Louisville. The Silurian Laurel Dolomite and Devonian Boyle Dolomite have both been producing dolomitic stone for several years. Although the demand is not great for dolomitic stone, this resource is available on the surface without having to be mined underground. Several quarries and mines operate in the area to provide aggregate for metropolitan Louisville and surrounding counties.