Central Kentucky Mineral District

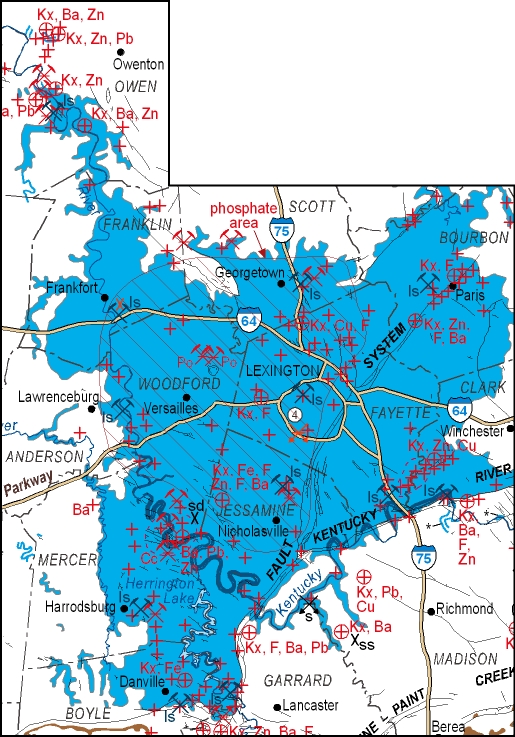

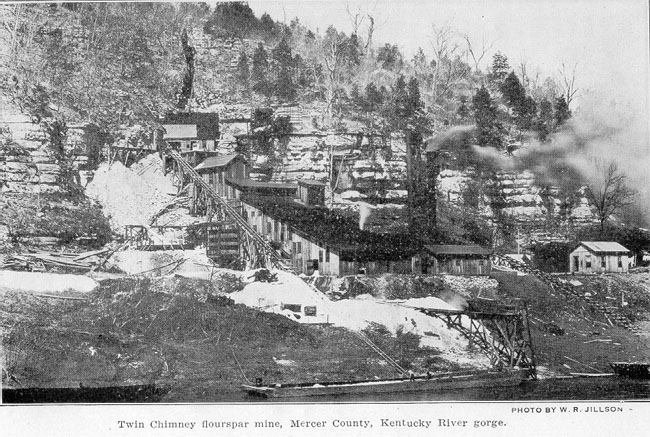

The Central Kentucky Mineral District, commonly known as the Central Kentucky Fluorspar District, covers part or all of the 16 counties in the Bluegrass Region of central Kentucky and consists of more than 200 vertically dipping vein deposits. Barite, fluorite, calcite, galena, and sphalerite have been sporadically mined in this district since 1900. All vein deposits cut through Ordovician carbonates along fractures and faults. During the early 1900s, major mines operated at Gratz in Owen County and Mundys Landing in Mercer and Woodford Counties. During World War I, mining activity took place at the Chinn, Faircloth, and Twin Chimney Mines in the Mundys Landing area, in the Boones Creek area in Fayette and Clark Counties, and in the Fayette-Scott-Bourbon County area. During World Wars I and II, sphalerite and galena were mined at Gratz in Owen County. During the 1960s, sphalerite and barite were mined from veins in Garrard, Lincoln, and Boyle Counties along the Dix River. In 1981, a vein deposit in the Lexington Quarry in Jessamine County was also mined for sphalerite. Exploration for deeper mineral potential in the Cambrian-Ordovician Knox Group has been conducted for several years and has yielded traces of metallic and nonmetallic minerals, although no commercial ore bodies have been discovered.

Vein Minerals

Mineral veins occur throughout central Kentucky, but are mostly concentrated along vertical, north-trending faults, fractures, and joints. More than 120 vein deposits have been documented (Anderson and others, 1982). Veins pinch and swell along strike, ranging from less than 1 foot in width to a maximum of 12 feet in width. Closely spaced veins 18 to 35 feet in width have been reported. Most of the veins are 100 to 1,000 feet in length, and two veins, the Gratz vein in Owen County and the Lexington Quarry vein in Jessamine County, have been traced for thousands of feet. The known vertical extent of the veins varies, but the Lexington Quarry, Gratz, and Chinn Mine (Mercer County) veins all exceed 300 feet.

There is a lateral mineral zonation in the district and maybe also a vertical zonation. Calcite and fluorite mineralization occurs in two central parts of the district, and barite, galena, and sphalerite occur in the outer parts of the district. Vertical zonation is more complex, because of the lateral zonation. Barite and galena appear to be more common in the Lexington Limestone, and sphalerite and galena are more common in the High Bridge Group.

The Gratz vein was mined in both world wars and produced sphalerite, galena, calcite, and barite. The concrete foundation for the mill and a calcite and barite tailings pond still remained on the property in 1990. Several shafts were opened on the vein, and some of them are still open. Most of the adits have caved in and are not accessible. The Gratz vein extends south into Henry County, where it is called the Cox vein. A shaft and adit were visible on this property in the 1990s. Detailed geologic investigations were conducted on these properties.

The Chinn Mine, Mercer County, operated in the early 1900s, and produced calcite and fluorite, with minor barite and sphalerite. Two shafts and an open-cut trench were opened on the vein, although many of the sites are now used as trash piles. Several cores were drilled on the property in the 1970s.

The Caldwell Stone Company Quarry intersected the Walker vein during its limestone mining operations, and although the company does not mine the vein for its mineral products, many rock and mineral collectors frequent the quarry to collect mineral specimens. This is private property, however, so permission from the owners must be obtained prior to entering the property.

Central Kentucky mineral veins contain barite, fluorite, calcite, sphalerite, galena, pyrite, chalcopyrite, and marcasite; some secondary carbonates including malachite, smithsonite, witherite, strontianite, and cerussite have also been observed or reported. The contacts between the veins and wall rock are generally sharp, and little or no wall alteration is observed except near the breccias, where dolomitization and breccia fragments are prevalent. Calcite and barite veinlets also occur in the wall rock adjacent to mineralized zones.

Because the veins occur in carbonate rocks on the flanks of an intercontinental basin with little or no associated igneous activity, and are associated with solution-collapse features, they are considered Mississippi Valley-type deposits (Ohle 1980). Mineralization in these types of deposits is the result of mineral-rich hydrothermal fluids being pushed out of the basin, upward toward the basin flanks. In the case of the Central Kentucky Mineral District, fluids from the Illinois Basin are thought to have migrated up the dip of the Cincinnati Arch to the crest of the arch on the Jessamine Dome. Isotopic analysis of minerals from central Kentucky suggests that the interaction of the hydrothermal fluids and sulfur from petroleum deposits in southern Kentucky may have aided in triggering precipitation of the minerals in Mississippi Valley-type deposits (Kesler and others, 1994).

The Lexington Quarry Vein Deposit, Jessamine County

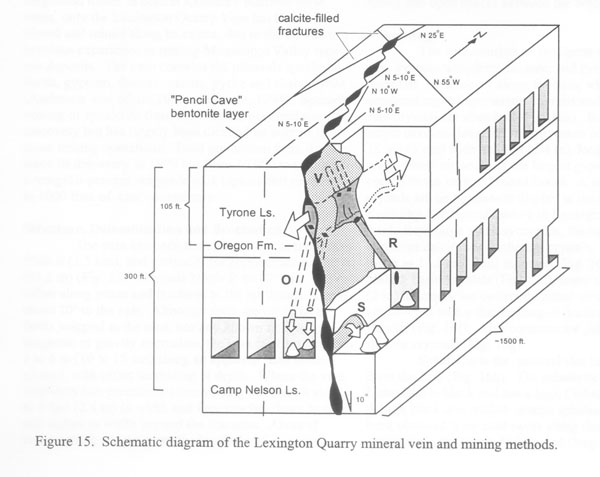

The Lexington Quarry is located 8 miles south of Lexington on Catnip Hill Road, west of the Norfolk-Southern Railroad in northern Jessamine County. The mineral vein is not exposed at the surface and was discovered in 1979 during excavation of air shaft no. 5 in the underground limestone mine. The vein occurs along a north-trending subsurface fault/fracture system in the High Bridge Group. Although numerous limestone quarries and underground mines in central Kentucky intersect these veins, only the Lexington Quarry vein has been explored and mined along its extent. The vein contains the minerals sphalerite, barite, gypsum, fluorite, calcite, pyrite, and chalcopyrite (Anderson and others, 1982; Anderson, 1994). Sphalerite from the vein has been mined sporadically since its discovery, but its exploitation has been dictated by normal limestone mining operations. Total production from the vein since its discovery in 1979 has been 10,000 tons of an average 10 percent ore-grade rock (sphalerite), resulting in 1,000 tons of zinc concentrate.

Structure, Dolomitization, and Brecciation

The vein has been traced laterally for more than 5,000 feet and vertically for approximately 300 feet. It trends north 5 to 10º east, and is offset along joints and fractures to the northwest. Dip is about 10º to the east. Although no surface faults are mapped in the area, and no regional aeromagnetic or gravity anomalies are known, the vein is offset between 4 and 6 inches along an apparent fault underground, with offset increasing at depth. Where the vein intersects two prominent crosscutting fractures, it swells to 8 feet in width and then pinches down to several inches in width beyond the fractures. Breccias occur in areas of crosscutting, which are filled and cemented with sphalerite with a grade of 5 percent (a higher grade than at other points along the vein).

Mineralization appears to be confined to the Tyrone Limestone below the Pencil Cave Bentonite, and does not extend upward into the overlying Lexington Limestone. Large amounts of sphalerite occur along the entire length of the vein immediately below the bentonite. The bentonite must have acted as a barrier to upward-migrating, mineral-rich fluids along the fault.

The contact between the vein and wall rock is dolomitizedand brecciated in the Tyrone, Oregon, and Camp Nelson formations. Dolomitization and brecciation are common features along faulted and fractured carbonates of the Bluegrass Region (Black and Haney, 1975). In the mine, there is dolomitization along the fault, and disseminated sphalerite occurs in the dolomitized wall rock adjacent to the vein. Solution brecciation and sphalerite replacement of limestone matrix is extensive. Dolomitization and brecciation increase from crackle breccia bodies along the wall rock to rubble breccia bodies near the center of the breccia.

Some of these breccia bodies are several feet wide and contain clasts of dolomite fragments and black sphalerite cemented with a matrix of reddish-brown sphalerite. Limestone clasts in the rubble breccia bodies locally are 10 inches in width, with extensive fracturing and open spaces between the breccia clasts.

Mineralogy

The vein consists of sphalerite with barite, calcite, gypsum/anhydrite, fluorite, and pyrite. At several locations, caves occur along the vein, containing exceptional crystal specimens. Fibrous and selenite gypsum crystals are abundant. In one of the larger cavities along the vein, gypsum crystals more than 18 inches wide and 8 feet long were discovered. These are some of the largest gypsum crystals recorded in the eastern United States. A set of these crystals is on permanent display in the lobby of the Kentucky Geological Survey's offices in Lexington. Aside from large gypsum crystals, the cavities also contain large calcite scalenohedral crystals (crystals whose faces are scalene triangles), which are as much as 7 inches in length. Blue bladed barite crystals, some as much as 2 inches in length, are common. Some of the barite crystals are covered with a thin coating (called a druse) of yellow-brown fluorite. Also common are yellow and purple fluorite crystals.

Sphalerite is the primary ore mineral that has been mined from the vein. The sphalerite in the Tyrone Limestone is black and has a high cadmium content, although black and reddish-orange sphalerite has also been obtained from mud caves along this vein. The sphalerite in the Tyrone, Camp Nelson and Oregon formation contain, cadmium. The high cadmium content in the Tyrone Limestone allowed it to be extracted from the sphalerite as well, which made the sphalerite in the Tyrone more economical to mine.

The northern part of the vein contains barite, gypsum, and sphalerite, and the southern part contains more calcite and sphalerite. A zone of replacement sphalerite, fluorite, and gypsum occurs near the center of the vein in a pinched zone where the vein turns and trends N10W. At the deepest level of mining (505 feet), in the Camp Nelson Formation, some hydrogen sulfide gas was observed along the vein. This gas may be a remnant from the fluids that produced the mineralization.